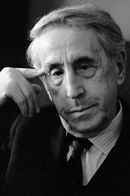

Abram Matveyevich Room was a renowned Soviet film director and screenwriter, born on June 28, 1894, in Vilna, with his real name being Abram Mordkhelevich Rom. He spent his early years studying at the St. Petersburg Bekhterev Psychoneurological Research Institute from 1914 to 1917, and later at the medical faculty of Saratov State University between 1917 and 1922.

Room's academic and professional journey continued as he worked in Saratov's arts department as a professor and rector of the Higher Theatrical Art Workshops from 1917. He then served as the director of Vsevolod Meyerhold's Theatre of the Revolution in Moscow from 1923, as well as the director and teacher of the Higher Pedagogical School of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee in the Kremlin.

Room's impressive career also saw him take on roles as the director at various studios, including Goskino, Sovkino, Soyuzkino, and Mosfilm, starting from 1924. Additionally, he taught as a senior lecturer at VGIK from 1925 to 1934.

One of Room's most notable films is the 1927 production "Bed and Sofa," which was written by Lev Kuleshov and Viktor Shklovsky. The film follows the story of a married woman who has an affair with their lodger, and explores the transformation of a housewife into a strong and liberated woman, which was unconventional for its time. Another notable title is the 1929 film "The Ghost That Never Returns."

Room's filmography includes "The Vodka Chase" (1924),which was his first directed film, as well as "The Plan for Great Works" (1930),a documentary that marked the first talking picture in the Soviet Union. His other notable works include "Traitor" (1926),"Ruts" (1928),"Criminals" (1933),"Squadron No. 5" (1939),"Invasion" (1945),"In the Mountains of Yugoslavia" (1946),"School for Scandal" (1952),"The Garnet Bracelet" (1964),"Late Flowers" (1969),and "A Man Before His Time" (1971).

Interestingly, Room was a vocal opponent of Sergei Eisenstein's concept, as stated in his essay "Moi kinoubezhdeniya" (My beliefs of film) in 1926. He believed that the living human should take priority in film, which was the opposite of Eisenstein's views.